Modern permaculture is a system design tool loosely based on the adage, 'Maximum contemplation, minimum action'. It is a way of:

1. looking at a whole system or problem;

2. observing how the parts relate;

3. planning to mend inefficient systems by applying ideas learned from long-term sustainable working systems; and,

4. seeing connections between key parts.

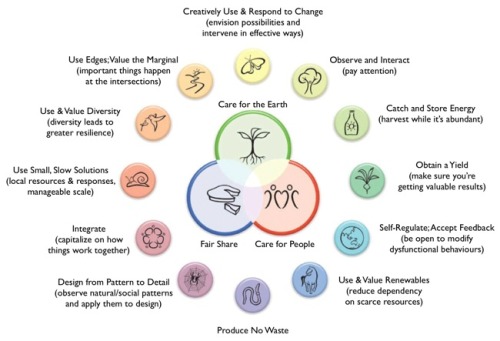

At the foundation of permaculture design are three ethical principles common to most traditional societies: care for the earth, care for people and fair share. As you can see from the image below, these ethical principles are very much at the centre of permaculture design, and they inform and underpin our consideration of each design principle.

|

| Permaculture Ethics and Design Principles |

The design principles themselves, as David Holmgren explains, 'are thinking tools that, when used together, allow us to creatively redesign our environment and our behaviour.'

Beginning with observation, we can move through each one, considering how all twelve design principles might apply to the task at hand. This process would naturally lead us back to where we started, 'reminding us that designing often involves many iterations or cycles before we are happy with an outcome.'

Intriguingly, permaculture principles lead to the conclusion that the most efficient way for people to flourish in the modern world is for the majority to live in towns and cities - reducing the amount of travelling needed - and to organise our food production cooperatively.

So much for the theory. See for yourself how TfL would score according to the twelve permaculture design principles:

i. Observe and Interact

For beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

|

| Photo credit: Joe D / Cotch.net |

ii. Catch and store energy

Make hay while the sun shines.

iii. Obtain a yield

You can't work on an empty stomach.

iv. Apply self-regulation and accept feedback

The sins of the fathers are visited on to the children unto the seventh generation.

v. Use and value renewable resources and services

|

| (Image from i b i k e l o n d o n) |

Remind me again, what are those things with the two wheels called? You know. The things with bells on. Ching, ching!

vi. Produce no waste

A stitch in time saves nine.

vii. Design from patterns to details

I am obviously delighted to learn this, but David Holmgren cautions, 'In any design process it is important to consider all twelve principles together, as they provide different perspectives that restrain and balance one another. Without an intuitive grounding in whole systems thinking, application of one of the design principles can lead to dysfunctional or even unethical decisions and actions. Nevertheless,' he continues, 'it is useful and often necessary to focus on one design principle at a time,' which is what we're doing now, so let's move on.

viii. Integrate

Many hands make light work.

ix. Use small, slow solutions

In other words, Slow and Steady Wins the Race. Just ask Jan Gehl if you don't believe me.

x. Use and value diversity

Don't put all your eggs in one basket.

xi. Use edges and value the marginal

Don't think you are on the right track just because it's a well-beaten path.

xii. Creatively use and respond to change

Vision is seeing things not as they are but as they will be.

|

| (Image from Vole O'Speed) |

I too am impatient for change. I first developed an interest for mass cycling in 1999. I had spent the summer hiring out bikes to people in Richmond Park, and was blown away to see so many smiles. These guys had just been for an eight-mile bike ride, and they loved every minute of it. Anyway, I began looking at other parks and things snowballed from there, really.

I too believe that current rates of cycling in this country are too low, that targets to increase them are miserably unambitious, and that a decent rate of cycling should be nearer 30 or 40% of all journeys. I too believe that this can only be achieved by the provision of dedicated safe cycle infrastructure, in line with the best practice found around the world. And finally, I too believe that this is worth it, because I too believe that cycling can contribute to making Britain a less congested, fitter, leaner, greener, cleaner, quieter and above all happier place.

Okay, I agree with all that. But how?

Let's remind ourselves what Andrew Davis said:

The difficulty is we're starting from here, and we as an organisation for twenty years have been pointing out that we're going to have a problem if we don't address things earlier. If you're dealing with these problems in a recession it's always very difficult for people to make changes: people are up against it, and so this is the last thing on their agenda, quite understandably, and that's why we've been warning, let's do it early, let's do it slowly, let's see what the targets are, and aim for them. It's ... the difficulty is in the big cities is probably the mix of how we travel is wrong. We need to encourage people to cycle and therefore we need to make the roads safe, and to do that you have to plan, not just one year, it's year on year, it's decade on decade, and other cities manage to do it, and we could do it too. It's very difficult to change the road layout for cyclists in a matter of months; it does take a long time planning, and it can be done, and it's done effectively across Europe.

And then:

The problem is that we are up against a war. If we took action twenty years ago it would be very gentle, but the later we leave it, the worse it's going to get for everyone, and we'll be dragged there screaming and kicking.

Whilst I agree with the first part, I don't agree that we need to be dragged there kicking and screaming. I know what the opinion polls routinely say. I imagine, if you asked the electorate, 'Would you like London to be a more cyclised city?', about 70 to 80 per cent would say, 'Yes!' We can show those people a vision of what the future might look like. We can do that.

David Arditti and marion (one of his correspondents) are both right of course: it is very hard to enthuse people about campaigning for the scraps which fall off the motorist lobby's table. The fact of the matter remains, however, we're not always making the best of what we've got. That's bad permaculture.

|

| Good permaculture |

I would be delighted to see London develop a European-style cycle network, such that any route could be used safely, of course I would. I acknowledge that this undertaking is an ambitious one, necessitating, as it does, a radical shift in the allocation of space on many main roads. But to focus only on this puts all our eggs in one basket, and also, crucially, ignores the margins, which 'are often the most valuable, diverse and productive elements in the system'.

I can show you what I mean by showing you a map of my six most often-used routes. You can see that I am mainly using so-called 'quiet' routes to get to the places that I want to get to. Unfortunately, and somewhat paradoxically, it becomes harder and harder to find these quiet routes out in the more remote suburbs.

Christian Woolmar: 'My gut instinct is that the £140m being spent on the [bike hire scheme and cycle superhighways] is not the best way to deliver cycling improvements in the city. The cycle hire scheme is in the mould of a grand projet, an attempt by a politician to grab the headlines with a high profile scheme, rather than doing the patient donkey work to slowly develop cycling. [...]

'I live in Islington where over the past decade or so, a cycling culture has emerged stimulated in great part by the efforts of the council. It is the road hump capital of the world, and that has changed the whole feel of the area. They have made it safe to cycle down roads which previously were death traps, attracting thousands of tentative cyclists back in the saddle. Seeing the streets dominated the other morning by the glorious combination of Lycra-clad and business-suited cyclists darting around the cycle routes, the back streets and the bus lanes is a testimony to a radical change that has taken place since I moved to the borough a decade and a half ago.

'This is very different from the cycling superhighways [...]. These are supposed to give cyclists direct routes into and out of central London along main roads but from the initial descriptions, they seem little more than a navigation scheme. Certainly, there seems to be nothing ‘super’ about them. They will [...] apparently be continuous, but there will be no segregated sections and virtually nothing will be done to help cyclists at difficult junctions. This too is designed to attract those lost cyclists with rotting bikes in their garages, but unlike in Islington, where the traffic has been slowed down, the philosophy at Transport for London under Boris Johnson is that all road users should have equal access to available space.

'Both cycle hire and superhighway have the feel of being rushed in to suit a political agenda, rather than being part of a sustained plan to boost cycling in the capital, especially as other [factors], such as cutting back spending on the London Cycling Network, [...] seem to be [taking us] in the opposite direction. I hope I am wrong and that both succeed in generating more cycling, but I suspect that there will have to be a considerable rethink about both projects before [we get more] bums on saddles.'

Azor_rider explained that we can improve subjective safety by encouraging local authorities to reduce speed differentials (more 20mph limits). Not that local authorities always need much encouraging. Southwark, for example, would open up all one-way streets to two-way cycle traffic as well as implement a 20mph speed limit on all residential streets. Fine, Boris says, as long as the people of Southwark are prepared to pay for it themselves. (Curious that he would say such a thing, when TfL so massively underspent.)

Azor_rider also suggested that we can develop cycle routes which run parallel to arterial roads, in the way that the Dutch do (i.e., by closing off rat runs but allowing 'permeability' for cyclists). Now, it has been pointed out to me that routes of this sort can suffer from lots of priority interruptions at junctions, but that's something that could be attended to. They can also be made much smoother in places.

|

| Do you come this way often? |

We should hope for more, I agree. As they say, Shoot for the moon, and you'll hit the top of the tree; shoot for the top of the tree, and you won't even get off the ground. That last was a note to self, by the way.

To learn more about Permaculture Design Principles, please click here.